In the Firminy-vert district, a church in the shape of a truncated pyramid marks the entrance to the last architectural complex designed by Le Corbusier.

The Saint-Pierre church in Firminy, France, is the third major religious building designed by Le Corbusier, after La Chapelle de Ronchamp and the Tourette convent church.

Its formal purity makes it one of Le Corbusier’s last great inspirations, even if the completed version differs in part from the original project approved by the architect a year before his death in 1965.

To be fair, it’s worth bringing José Oubrerie, Le Corbusier’s assistant architect, out of the shadows. He had to reinterpret the master’s creation and adapt it to technical and financial constraints, overseeing its construction for over 30 years, until its completion in 2006.

The architecture of Firminy’s Saint-Pierre church, in pathways

The path of shapes

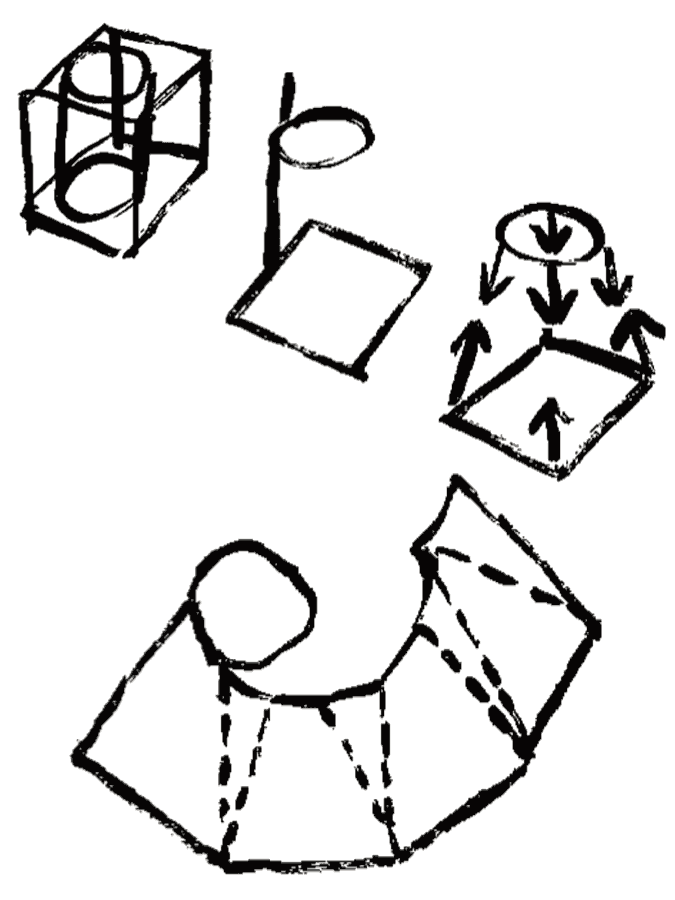

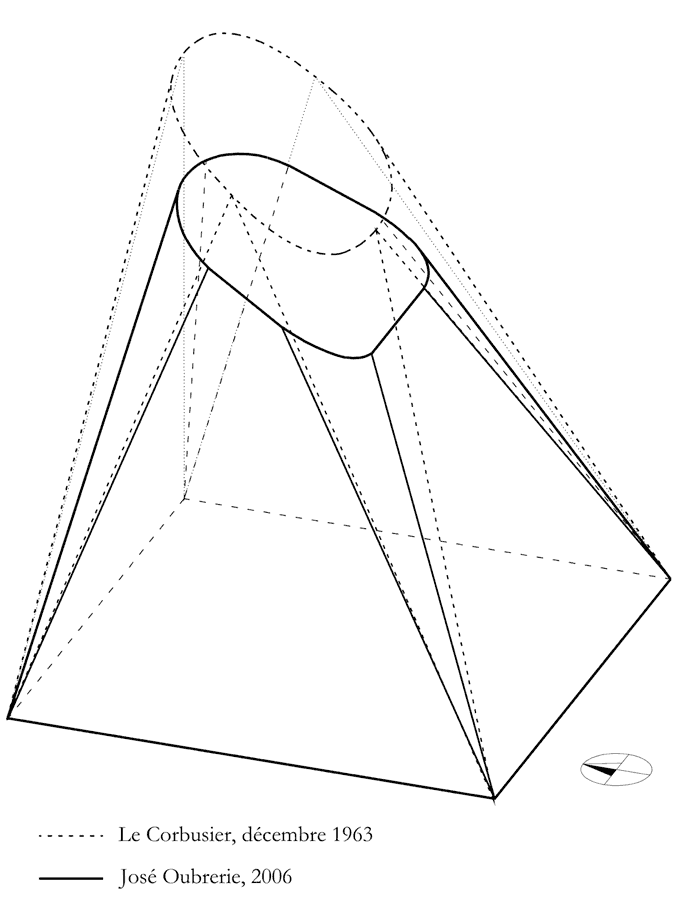

Between Le Corbusier’s original idea of transforming a rounded shape into a square, and José Oubrerie’s realization, the shape of the church may appear to have retained a fairly similar appearance, but its nature has changed fundamentally.

The transformation of a round into a square implies a continuous ovoid curve, which is extremely complex to achieve in architecture, especially at the time it was conceived, in the 1960s.

Oubrerie has redesigned the hull with flat sections joined by curves, creating a pyramidal rather than ovoid shape.

Oubrerie bevelling

For this “lifetime project” as chief architect, José Oubrerie had to make choices in relation to the project defined by Le Corbusier.

This meant, for example, increasing the size of the square base, reducing the height of the church, and redefining the angle of the roof’s mitre from 46° to 34°!

With the abandonment of the main concept of the ovoid shape, the Firminy “pyramid” is not quite Le Corbusier’s creation.

Pyramid-shaped Saint-Pierre church, Firminy

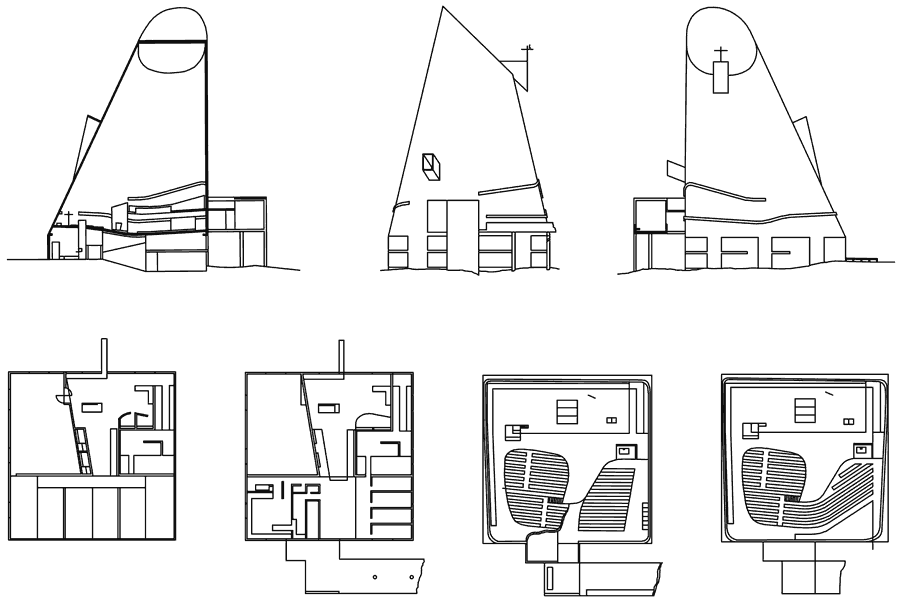

The church is characterized by its truncated cone, formed by 4 sections of trapezoidal concrete walls, reaching a height of 33 metres with a square base measuring 25 metres on each side.

Sharp at the base, the edges become increasingly rounded as the “pyramid” rises.

This rather unique concrete shell involved the creation of over a hundred formworks, which were only used once!

85 corner formworks were created in wood, with the help of 3D software in the early 2000s, resolving the complexity of the curved sections. The formwork for the flat sections was made of metal.

Water paths

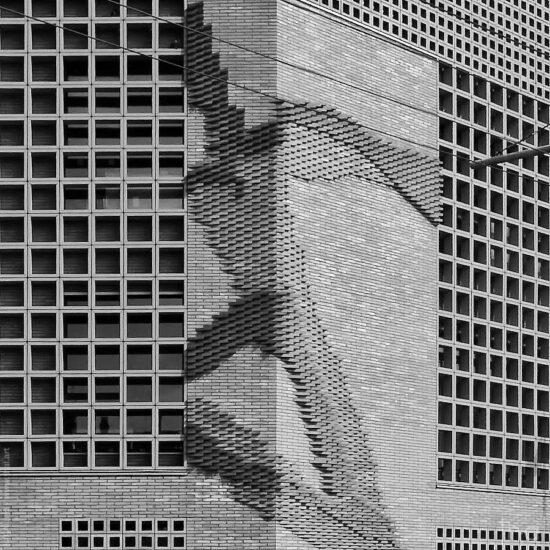

Highly visible and emphasized by concrete frames, the water paths form the decorative grid that enlivens the facades and helps make the building unique.

The bevelled top of the Saint-Pierre church in Firminy means that only a large vertical gutter is visible on the south facade to evacuate rainwater from the roof.

On the sides of the church, two other horizontal concrete-framed gutters are positioned at different heights to collect all the water flowing from the cone, which is divided into two basins on the south and north sides.

On the east facade, a curved canopy distributes some of the rainwater, which is collected on either side by the lower gutter.

Paths of light

The cannons

The two round and square light cannons on the roof, as well as the bell tower, were cast in the ground, then hoisted and held in place before being integrated into a 36 cm thick concrete slab that acts as the keystone.

On the west side, a third, rectangular-shaped light cannon is fixed in an almost horizontal position, accompanied by tinted glass fenestrons at the bottom and large windows extending on three sides of the base.

The “glass holes”

On the east facade, a multitude of small glass perforations allow morning light to pass through the cone.

Invisible loopholes

Hidden on the façade behind the concrete bands of the water drainage channels, a string of small downward-bevelled “skylights” encircle the entire church.

The Men’s Path

As is often the case, Le Corbusier takes us on an architectural promenade, with an external access ramp running around the south façade, allowing us to admire the entire church with its lower section, and then to enter the nave directly via a main entrance on the west façade.

Another entrance, topped by a canopy on the east side of the plinth, provides access to the exhibition areas.

The religious path

Although the church was originally designed for a bishopric, this soon withdrew for financial reasons, before construction began.

With funding provided mainly by the Saint-Etienne local authority, the church has become more of a tourist attraction in honor of Le Corbusier, even if it still holds occasional masses.

The interior of Saint-Pierre church, highlighted

The first two levels under the church are wide open to the light. These include the reception area, several exhibition rooms belonging to the Musée d’Art Moderne de Saint-Etienne, and a conference room.

Apart from concerts and masses, entry to the church (for a fee) is usually via an interior staircase (which was to have been a ramp in Le Corbusier’s original design).

If you look up, you’ll get a first, purely architectural view of the space, without the religious signs, and a glimpse of some of the lighting designed by the architect.

Two light cannons on the south-facing ovoidal roof slab provide zenithal light for most of the day.

The interplay of light and chance

At certain times of the day, a multitude of beams of light, whose source is indistinguishable, draw a tangle of curves on the walls that one might believe to be of divine origin.

The explanation for the phenomenon is more prosaic, and does not originate in the brain of the brilliant architect. It is very simply explained by the site manager:

“Normally, the plan was to use smooth polymethacrylate light cannons, but we chose cannons with small notches to improve adhesion. We made this choice as a precaution. It’s these little notches that draw large circles of light inside the church. It’s spectacular.

Inside, sunrise side

In the morning, dozens of tiny lights above the altar pierce the wall through the perforations visible on the eastern facade.

Although Le Corbusier had envisaged these small luminous holes in his project (rather with colored glass), he didn’t have the opportunity to decide on their exact layout during his lifetime. So it was architect José Oubrerie, in agreement with his client, the metropolis of Saint-Étienne, who decided to represent the constellation of Orion, a constellation that has no religious reference and is visible in both hemispheres of the earth.

The encirclement of skylights

Hidden openings in the façade reveal their coloured bands around the perimeter of the room. They illuminate most entrances, even at night, thanks to interior lighting.

Intérieur, côté soleil couchant

The green-blue light cannon on the west side is positioned almost horizontally to illuminate the high altar at the end of the day.

Skylights

The Firminy church features several variations of skylights, which Le Corbusier favored for places of worship as well as in his houses, such as the interior of the Villa Savoye and the Maison La Roche.

The cannons, which protrude imposingly from both the interior and exterior of the facades, increase the light source and concentrate the light beam at the same time, depending on their depth.

In some buildings, they are placed horizontally, and can even be explored on foot, as in Bernard Zehrfuss’s Lugdunum underground museum in Lyon, France.

You may be interested in other reports on Le Corbusier architect:

Acoustics at fault

The church’s acoustics produce a resonance of the order of 11 seconds, making classical music concerts impossible. Only contemporary creations created expressly for this venue can be performed here.

40 years of twists and turns

The project presented by Le Corbusier in 1964, a year before his death, would take almost 10 years to get off the ground under the direction of his assistant José Oubrerie, due to the withdrawal of the bishopric, the original sponsor.

The first project for Saint-Pierre church was undertaken by a local association and began in 1973.

This was followed by five eventful years, with the project being halted and resumed several times until 1978.

In 1996, the walled and largely unfinished building, with only its base, was listed as a historic monument in order to protect it and its surroundings.

Construction finally resumed 7 years later, in 2003, financed by the Saint-Étienne metropolitan authority and under the supervision of the Le Corbusier Foundation, before delivery in 2006.

The church was inaugurated on November 29, 2006, and will remain the only Le Corbusier building to be erected in the 21st century.

All you need to know about the original?

A vertical face, a larger size, a shape composed of hyperboloid surfaces, an interior access ramp, … all of Le Corbusier’s ideas that were abandoned.

As for the details, architect José Oubrerie also declared in an interview that the hundredths-scale plans left by the studio gave him a great deal of room for manoeuvre.

To learn all about the differences between Le Corbusier’s original project and José Oubrerie’s final realization, I recommend this article: forty years of history between idea and realization.

Thierry Allard

French photographer, far and wide

Please respect the copyright and do not use any content from this article without first requesting it.

If you notice any errors or inaccuracies in this article, please let me know!